Open Democracy (UK) chronique Lost Land (Territoire perdu)

By Bérengère Sims.

A long-forgotten wall: the struggle of the Sahrawi people.

Lost Land exposes the painful reality of the Sahrawi people, whose homeland is occupied by Morocco, while they crave independence.

At the Open City Documentary Festival on 7th September 2017.

Some politicians enjoy talking about walls; they seem to be all the rage. The most recent example would have to be American president Donald Trump’s obsession with building a wall along the US-Mexico border; since the second intifada in 2000, Palestinians have found themselves trapped by the Israel West Bank barrier; and, not so far from home, in the European Union – facing the worst refugee crisis since World War Two – walls have mushroomed despite the Schengen Agreement’s supposed abolishing of internal borders.

Lost Land, or Territoire Perdu, a documentary by Belgian writer and director Pierre-Yves Vandeweerd, sheds light on a lesser known, but equally oppressive, wall: el hisam – ‘the belt’ in Arabic.

El hisam is the word used to refer to the wall built by Moroccans in the Western Sahara. It stretches over 2,400 km and cuts the Sahrawi territory into two parts: one part is occupied by Morocco and the other is controlled by the Sahrawi People’s Liberation Army.

This wall, unlike those listed above, has not benefited from the same degree of press coverage; Vandeweerd’s documentary, released in 2011, is a raw testimony to the suffering of the Sahrawi people, and the nomadic lifestyle they preserve, compressed between Mauritania and Morocco.

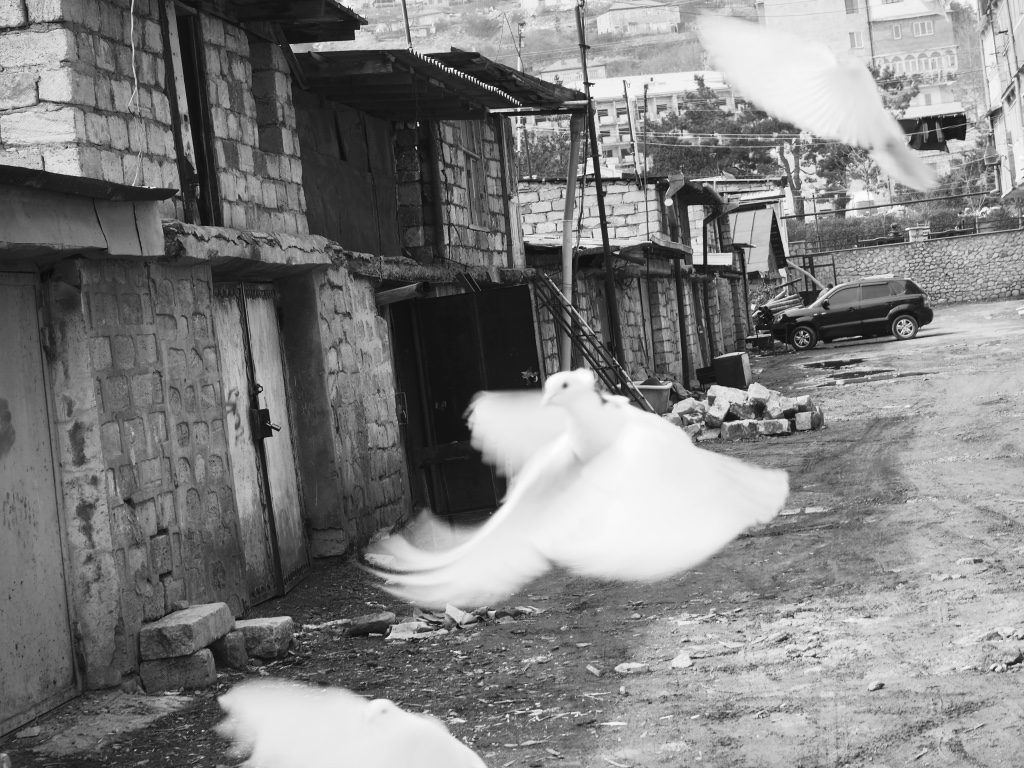

Lost Land has a nostalgic feel: it is a collection of stills, sometimes of the arid and empty desert landscape and sometimes portraits of the Sahrawi people, filmed with Super 8 cameras (a Kodak model that was introduced in 1965 and is best known for making home movies accessible to the masses).

Throughout the black and white 75-minute long documentary, nine people tell their stories of the occupation. Some were alive in 1975 when the raids first occurred and had to escape to Moukhayyem, the strip of desert that Algeria handed over to the Sahrawi for makeshift refugee camps; some are children of the disappeared; some are activists who have been tortured for participating in peaceful protests for their independence.

One activist, her voice shaking, recalls what a police officer said to her before she was tortured: “maybe you’ll get independence but no Sahrawi will have the pleasure of seeing that day. We’ll kill you like we killed your parents in 1976.”

The violations they recount are rendered the more chilling by the film’s soundtrack: the sound of wind whipping through the desert; a distant morning radio show on the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic Radio crackles; braying camels echo through the vast landscape.

These auditory punctuations in the narrative, coupled with stills of the desert landscape, build feelings of nostalgia – of the heavy burden of waiting, and of the Sahrawi’s ongoing wait to return their lives before the occupation. The power of their testimonies intertwined with the intensity of the filmed portraits of the victims results in an intimacy which makes the viewer feel they are invited into the heart of this little-known conflict.

Vandeweerd guides the viewer through the history of the conflict with informative pauses: a beige screen appears with a word (such as el hisam) in Arabic, with its English translation, and a short paragraph explaining what this word means to the Sahrawi people.

This gears the documentary towards an audience prepared to do a bit of homework. He also only shows one side of the conflict, which leaves the viewer wondering what the other side of the wall looks like and how it is perceived in Morocco.

That said, the testimonies Vandeweerd captures convey a powerful message. Uttered by an older woman sitting on the floor, recounting the brutal events of 1975, this testimony stuck with me: “The Moroccans killed our children. They killed our brothers, our husbands, our loved ones. We were alone and defenseless. But we had one hope: returning to our land, freed from the people who had attacked us.”

www.opendemocracy.net (20 of September 2017)

OpenDemocracy is an independent global media platform covering world affairs, ideas and culture which seeks to challenge power and encourage democratic debate across the world.